Abstract

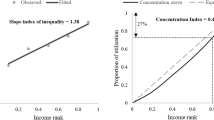

A number of recent findings from the literature imply that the value of a QALY varies depending on the concentration or dispersion of that QALY over treated individuals. Given that funding decisions are currently made under either the assumption of distributive-neutrality or some combination of explicit decision criteria and implicit adjustment for distributional concerns, it is likely that substantial social welfare gains are available if distributional objectives could be more accurately reflected in funding decisions. This paper considers three alternative approaches to explicitly adjust for distributional concerns with regard to the concentration or dispersion of individual health gains.

Including non-health arguments in the objective function by #x2018;weighting’ QALYs for distributional effects or imposing differential funding thresholds for interventions with different distributional effects might be considered first- and second-best solutions, and would likely deliver the greatest social welfare gains. However, there is some doubt that first- or second-best solutions would be: (i) feasible given current data gaps; and (ii) politically acceptable. Rather, a simple and transparent approach is suggested wherein the sponsors of interventions that deliver health gains that are of questionable ‘welfare-significance’ for the treated individual would be required to provide decision-makers with an estimate of willingness to pay for the QALYs in question and would only be eligible for funding in the event that the positive net present value criterion is met.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

1 21% of respondents assigned equivalent social value to 1 year of benefit for 100 persons and to 20 years of benefit for fewer than 5 persons. In comparison, 14% of respondents assigned equivalent social value to 2 years of benefit for 100 persons and to 20 years of benefit for fewer than 10 persons. 18% of respondents assigned equivalent social value to 5 years of benefit for 100 persons and to 20 years of benefit for fewer than 25 persons.

2 The rationale for specific egalitarianism with respect to healthcare stems from the characteristics it has in consumption. In particular, healthcare confers — to a greater or lesser extent — ‘good health’ and, hence, the distribution of healthcare has implications for the distribution of health. As Culyer and Wagstaff[10] put it, “the demand for equality in healthcare is a derived demand from the equality of health” (p. 432).

References

Dolan P, Shaw R, Tsuchiya A, et al. QALY maximisation and people’s preferences: a methodological review of the literature. Health Econ 2005; 14: 197–208

Olsen JA. A note on eliciting distributive preferences for health. J Health Econ 2000; 19: 541–550

Choudhry N, Slaughter P, Sykora K, et al. Distributional dilemmas in health policy: large benefits for a few or smaller benefits for many? J Health Serv Res Policy 1997; 2 (4): 212–216

Pinto-Prades JL, Lopez-Nicol A. More evidence on the plateau effect. Med Decis Making 1998; 18: 287–316

Rodriguez-Miguez E, Pinto-Prades JL. Measuring the social importance of concentration or dispersion of individual health benefits. Health Econ 2002; 11: 43–53

Olsen JA, Heiberg I. Applying the person trade-off method to derive equity weights: the case of remaining life years. The World Congress of the International Health Economics Association (iHEA); 1996 May 19–23; Vancouver

Johannesson M, Johansson PO. Is the valuation of a QALY gained independent of age? Some empirical evidence. J Health Econ 1997; 16 (5): 589–599

Maynard A. Rationing health care: what use citizens’ juries and priority committees if principles of rationing remain implicit and confused? BMJ 1996; 313 (7071): 1499–1501

Wagstaff A. QALYs and the equity-efficiency trade-off. J Health Econ 1991; 10: 21–41

Culyer AJ, Wagstaff A. Equity and equality in health and health care. J Health Econ 1993; 12: 431–457

Nord E, Richardson J, Street A, et al. Maximising health benefits vs egalitarianism: an Australian survey of health issues. Soc Sci Med 1995; 41 (10): 1429–1437

Institute of Medicine. New vaccine development: establishing priorities. Vol. II: diseases of importance in developing countries. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1986

Lewis PA, Charny M. Which of two individuals do you treat when only their ages are different and you can’t treat both? J Med Ethics 1989; 15: 28–34

Murray C. Rethinking DALYs. In: Murray C, Lopez AD, editors. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assess-ment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge (MA): WHO, Harvard University Press, 1996

Johannesson M, Gerdtham U-G. A note on the estimation of the equity-efficiency trade-off for QALYs. J Health Econ 1996; 15: 359–368

Olsen JA. Persons vs years: two ways of eliciting implicit weights. Health Econ 1994; 3: 39–46

Llewellyn-Thomas H, Sutherland III, Tibshirania R. Describing health states: methodological issues in obtaining values for health states. Med Care 1984; 22: 543–52

Gilson L. Government health care charges: is equity being abandoned? London: Evaluation and Planning Centre for Health Care, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 1988

Olsen JA. Aiming at what? The objectives of the Norwegian health service. In: Alban A, Christiansen T, editors. The nordic health care system. Odense: Odense University Press, 1994

Broome J. Trying to value a life. J Public Econ 1978; 9: 91–100

George B, Harris A, Mitchell A. Cost-effectiveness analysis and the consistency of decision making: evidence from pharmaceutical reimbursement in Australia (1991 to 1996). Pharmacoeconomics 2001; 19: 1–8

Ng Y-K. Welfare economics: introduction and development of basic concepts. Rev. ed. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, 1983

Nord E. The trade-off between severity and treatment effect in cost-value analysis of health care. Health Policy 1993; 24: 227–38

Nord E, Pinto JL, Richardson J, et al. Incorporating societal concerns for fairness in numerical valuations of health programs. Health Econ 1999; 8: 25–39

Stolk EA, van Donselaar G, Brouwer WBF, et al. Reconciliation of economic concerns and health policy: illustration of an equity adjustment procedure using proportional shortfall. Pharmacoeconomics 2004; 22 (17): 1097–107

Barendregt JJ, Bonneux L, Van der Maas PJ. DALYs: the age-weights on balance. Bull World Health Organ 1996; 74 (4): 439–43

Qlsterdal LP. A note on cost-value analysis. Health Econ 2003; 12 (3): 247–50

Anand S, Hanson K. Disability-adjusted life years: a critical review. J Health Econ 1997; 16: 685–702

Dolan P, Cookson R, Ferguson B. Effect of discussion and deliberation on the public’s views of priority setting in health care: focus group study. BMJ 1999; 318: 916–9

Department of Health and Ageing. Other relevant factors and the “rule of rescue”: ratified at the March 2003 meeting of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee meeting; 2004; Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra [online]. Available from URL: http://www.dhac.gov.au/intemet/wcms/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pbs-general-pubs-pharmpacrelevant.htm-copy2 [Accessed 2005 Oct 26]

Hadorn D. Setting health care priorities in Oregon: cost-effectiveness meets the rule of rescue. JAMA 1991; 265 (17): 2218–25

Department of Health and Ageing. Guidelines for the pharmaceutical industry on preparation of submissions to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee including Major submissions involving economic analyses: September 2002. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2002 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.dhac.gov.au/intemet/wcms/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pbs-general-pubs-guidelines-content.htm [Accessed 2005 Oct 26]

Wonder M, de Abreu Lourenco R. Factors considered in pharmaceutical reimbursement in Australia: a role for the rule of rescue? Paper presented at ISPOR First Asia-Pacific Conference; 2003 Sep 1–3; Kobe [online]. Available from URL: https://www.ispor.org/conferences/kobe09O3/finPROGRAM.pdf [Accessed 2005 Oct 26]

Olsen JA, Smith RD. Theory versus practice: a review of willingness to pay in health and health care. Health Econ 2001; 10: 39–52

Donaldson C, Shackley P. Willingness to pay for health care. In: Scott A, Maynard A, Elliott R, editors. Advances in health economics. London: John Wiley, 2003

Shackley P, Donaldson C. Using willingness to pay to elicit community preferences for health care: is an incremental approach the way forward? J Health Econ 2002; 21: 971–91

Ryan M. Using conjoint analysis in health care to elicit patients’ preferences. London: Office of Health Economics, 1996

Smith RD, Olsen JA, Harris A. Resource allocation decisions and the use of willingness-to-pay as a valuation technique within economic evaluation: recommendations from a review of the literature. Melbourne (VIC): Centre for Health Program Evaluation, Monash University, 1999

Hjelmgren J, Berggren F, Andersson F. Health economic guidelines: similarities, differences and some implications. Value Health 2001; 4 (3): 225–50

Cookson R. Willingness to pay methods in health care: a sceptical view. Health Econ 2003; 12: 891–4

Acknowledgements

The Centre for Health Economics at Monash University provided the necessary financial support to allow completion of this paper but the views expressed herein are the sole responsibility of the author. The author would like to thank two anonymous referees for useful comments on an earlier draft. The author has no competing interests to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mortimer, D. The Value of Thinly Spread QALYs. Pharmacoeconomics 24, 845–853 (2006). https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200624090-00003

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200624090-00003